Hinduism in the Philippines

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| Scriptures | |

| Bhagavad Gita, Mahabharata, Upanishads | |

| Languages | |

| Indo-Aryan languages (Sanskrit, Hindi and Sindhi), Butuanon, English, Ibanag, Kapampangan, Pangasinense, Tagalog, Visayan |

| Hinduism by country |

|---|

|

| Full list |

Recent archaeological and other evidence suggests Hinduism has had some cultural, economic, political and religious influence in the Philippines. Among these is the 9th century Laguna Copperplate Inscription found in 1989, deciphered in 1992 to be Kawi script (from Pallava script) with Sanskrit words;[2] the golden Agusan statue (Golden Tara) discovered in another part of Philippines in 1917 has also been linked to Hinduism.[3]

Hinduism today

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2014) |

There is some growth in the religion as of late, although most temples cater to the same communities. Actual adherents of Hinduism are mostly limited to communities that include indigenous and native peoples, expatriate communities, as well as new converts. There are various ISKCON groups and popular Hindu personalities and groups such as Sathya Sai Baba, and Paramahansa Yogananda (SRF), Prabhat Ranjan Sarkar (Ananda Marga) that can be found. The Ramakrishna Mission is also present as the Vedānta Society of the Philippines.[4] Hindu based practices like Yoga and meditation are also popular. There are also notable archery ranges named after characters in the Ramayana and the Mahabharata called "Kodanda Archery Range" (named after Lord Rama's bow Kodanda) and "Gandiva Archery" (named after Arjuna's bow Gandiva).

One source estimated the size of the Indian community in the Philippines in 2008 at 150,000 people, most of whom are Hindus and Christians.

At present, however, it is limited primarily to the immigrant Indian community and local Butuanon people, though traditional religious beliefs in most parts of the country have strong Hindu and Buddhist influences.

Over the last three decades, a large number of civil servants and highly educated Indians working in large banks, Asian Development Bank and the BPO sector have migrated to Philippines, especially Manila. Most of the Indian Filipinos and Indian expatriates are Hindu, Sikh or Muslims, but have assimilated into Filipino culture and some are Catholic . The community regularly conducts philanthropic activities through bodies such as the Mahaveer foundation, The SEVA foundation and the Sathya Sai organization. Most Hindus congregate for socio-cultural and religious activities at the Hindu Temple (Mahatma Gandhi Street, Paco, Manila), and the Radha Soami Satsang Beas center (Alabang, Muntinlupa, Metro Manila).

History

[edit]

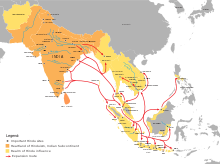

The archipelagos of Southeast Asia were under the influence of Hindu Tamil Nadu and Indonesian traders through the ports of Malay-Indonesian islands. Indian religions, possibly an amalgamated version of Hindu-Buddhist arrived in Philippines archipelago in the 1st millennium, through the Indonesian kingdom of Srivijaya followed by Majapahit. Archeological evidence suggesting exchange of ancient spiritual ideas from India to the Philippines includes the 1.79 kilogram, 21 carat gold Hindu goddess Agusan (sometimes referred to as Golden Tara), found in Mindanao in 1917 after a storm and flood exposed its location.[5] The statue now sits in the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, and is dated from the period 13th to early 14th centuries.

A study of this image was made by Dr. F. D. K. Bosch, of Batavia, in 1920, who came to the conclusion that it was made by local workmen in Mindanao, copying a Ngandjuk image of the early Madjapahit period – except that the local artist overlooked the distinguishing attributes held in the hand. It probably had some connection with the Javanese miners who are known to have been mining gold in the Agusan-Surigao area in the middle or late 14th century. The image is apparently that of a Sivaite goddess, and fits in well with the name "Butuan" (signifying "phallus").

— H. Otley Beyer, 1947[3]

Juan R. Francisco suggests that the golden Agusan statue may be a representation of goddess Sakti of the Siva-Buddha (Bhairava) tradition found in Java, in which the religious aspect of Shiva is integrated with those found in Buddhism of Java and Sumatra. Butuan, in present-day Agusan del Norte in Butuan, used Hinduism as its main religion along with indigenous animism. A Hindu Tamil-Malay king of Cebu was also recorded.[6] In the nearby kingdom of Sanmalan in the Zamboanga Peninsula, the Chinese recorded a tribute mission from its ruler named Rajah Chulan.[7][8]

Another gold artifact, from the Tabon Caves in the island of Palawan, is an image of Garuda, the bird who is the mount of Vishnu. The discovery of sophisticated Hindu imagery and gold artifacts in Tabon Caves has been linked to those found from Oc Eo, in the Mekong Delta in Southern Vietnam.[9] These archaeological evidence suggests an active trade of many specialized goods and gold between India and Philippines and coastal regions of Vietnam and China. Golden jewelry found so far include rings, some surmounted by images of Nandi – the sacred bull, linked chains, inscribed gold sheets, gold plaques decorated with repoussé images of Hindu deities.[9][10]

In 1989, a laborer working in a sand mine at the mouth of Lumbang River near Laguna de Bay found a copper plate in Barangay Wawa, Lumban.[5] This discovery, is now known as the Laguna Copperplate Inscription by scholars. It is the earliest known written document found in the Philippines, dated to be from the 9th century AD, and was deciphered in 1992 by Dutch anthropologist Antoon Postma.[2] The copperplate inscription suggests economic and cultural links between the Tagalog people of Philippines with the Javanese Medang Kingdom, the Srivijaya empire, and the Hindu-Buddhist kingdoms of India. Hinduism in the country declined when Islam was introduced by traders from Arabia which was then followed by Christianity from Spain.[5] This is an active area of research as little is known about the scale and depth of Philippine history from the 1st millennium and before.

Folklore, arts and literature

[edit]Many fables and stories in Filipino Culture are linked to Indian arts, such as the story of the monkey and the turtle, the race between deer and snail (slow and steady wins the race), and the hawk and the hen. Similarly, the major epics and folk literature of Philippines show common themes, plots, climax and ideas expressed in the Mahabharata and the Ramayana.[11]

According to Indologists Juan R. Francisco and Josephine Acosta Pasricha, Hindu influences and folklore arrived in Philippines by about 9th to 10th century AD.[12] There is a Maranao version of the Hindu Epic Ramayana known as Maharadia Lawana (King Rāvaṇa[13]).

Language

[edit]With the advent of Spanish colonialism in the 16th century, the Philippines became a closed colony and cultural contacts with other Southeast Asian countries were limited, if not closed. In 1481, the Spanish Inquisition commenced with the permission of Pope Sixtus IV and all non-Catholics within the Spanish empire were to be expelled or to be "put to the question" (tortured until they renounced their previous faith). With the re-founding of Manila in 1571, the Philippines became subject to the King of Spain, and the Archbishop of New Galicia (Mexico) became the Grand Inquisitor of the Faithful in Mexico and the Philippines. In 1595, the newly appointed Archbishop of Manila became the Inquisitor-General of the Spanish East Indies (i.e., the Philippines, Guam, and Micronesia), and until 1898 was active against Protestants, Buddhists, Hindus and Muslims. As was the case in Latin America and Africa, forced conversion was common and any refusal to submit to Church authority was seen as both rebellion against the Pope and sedition against the Spanish Crown, which was punishable by death.[citation needed]

Linguistic influence left lasting marks on every Philippine language. Below are some borrowed terms, which were often Buddhist and Hindu concepts, with the original Sanskrit; some of the words in many Philippine languages are loaned from Sanskrit and Tamil.[14] The conservative nature of these loanwords and shared correspondence with Malay suggest that many of these loanwords were borrowed from an earlier form of Classical Malay that preserved the distinction between several Sanskrit phonemes.[15]

Tagalog

[edit]

- budhî "conscience" from the Sanskrit bodhi

- Bathalà "bhattara – Hindu God Shiva" from the Sanskrit Bhattara

- dalità "one who suffers" from the Sanskrit dharita

- dukhâ "poverty" from the Sanskrit dukkha

- guró "teacher" from the Sanskrit guru

- sampalatayà "faith" from the Sanskrit sampratyaya

- mukhâ "face" from the Sanskrit mukha

- lahò "eclipse", "disappear" from the Sanskrit rahu

- maharlika "noble" from Sanskrit mahardikka

- saranggola "kite" from Sanskrit layang gula (via Malay)

- bagay "thing" from Tamil "vagai"

- talà "star" from Sanskrit tara

- puto, a traditional rice pastry, from Tamil puttu (via Malay)

- malunggay "moringa" from Tamil "murungai"

- saksí "witness" from Sanskrit saksi

Kapampangan

[edit]- kalma "fate" from the Sanskrit karma

- damla "divine law" from the Sanskrit dharma

- mantala -"magic formulas" from the Sanskrit mantra

- upaya "power" from the Sanskrit upaya

- lupa "face" from the Sanskrit rupa

- sabla "every" from the Sanskrit sarva

- lawu "eclipse" from the Sanskrit rahu

- Galura "giant eagle (a surname)" from the Sanskrit garuda

- Laksina "south" (a surname) from the Sanskrit dakshin

- Laksamana/Lacsamana/Laxamana "admiral" (a surname) from the Sanskrit lakshmana

Cebuano

[edit]- asuwang "demon" from Sanskrit asura

- balita "news" from Sanskrit varta

- bahandi "wealth" from Sanskrit bhandi

- baya "warning to someone in danger" from Sanskrit bhaya

- budaya "culture" from Sanskrit; combination of boddhi, "virtue" and dhaya, "power"

- diwata "goddess" from Sanskrit devata

- gadya "elephant" from Sanskrit gajha

- puasa "fasting" from Sanskrit upavasa

- saksí "witness" from Sanskrit saksi

Tausūg

[edit]- suarga "heaven"; compare sorga in modern Indonesian

- agama "religion"

Ibanag

[edit]- karahay a cooking pan similar to the Chinese wok, from the Sanskrit karahi

- tura the word meaning "to write" came from the Sanskrit sutra meaning literature or scripture

- kapo the word cotton from Sanskrit kerpas

Common to many Philippine languages

[edit]- sutlá "silk" from the Sanskrit sutra

- kapas "cotton" from the Sanskrit kerpas

- naga "dragon" or "serpent" from the Sanskrit nāga

Hindu temples

[edit]- Hari Ram Temple (Paco, Manila)

- Saya Aur Devi Mandir Temple (Paco, Manila)

- Indian Hindu Temple (Cebu City)

- Baguio Hindu Temple (Baguio City)

- Davao Indian Temple (Davao City), it also contains a Sikh Gurdwara.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Philippines, Religion And Social Profile". thearda.com. Retrieved June 25, 2024.

- ^ a b Postma, Antoon. (1992), The Laguna Copper-Plate Inscription: Text and Commentary, Philippine Studies, 40(2):183–203

- ^ a b H. Otley Beyer, "Outline Review of Philippine Archaeology by Islands and Provinces," Philippine Journal of Science, Vol.77, Nos. 34 (July–August 1947), pp. 205–374

- ^ "Branch Centres - Belur Math - Ramakrishna Math and Ramakrishna Mission".

- ^ a b c Golden Tara Archived November 2, 2014, at the Wayback Machine Government of the Philippines

- ^ Juan Francisco (1963), A Note on the Golden Image of Agusan, Philippine Studies vol. 11, no. 3 (1963): 390—400

- ^ John N. Miksic (September 30, 2013). Singapore and the Silk Road of the Sea, 1300_1800. NUS Press. pp. 147–. ISBN 978-9971-69-574-3.

- ^ Marie-Sybille de Vienne (March 9, 2015). Brunei: From the Age of Commerce to the 21st Century. NUS Press. pp. 47–. ISBN 978-9971-69-818-8.

- ^ a b Anna T. N. Bennett (2009), Gold in early Southeast Asia, ArcheoSciences, Volume 33, pp 99–107

- ^ Dang V.T. and Vu, Q.H., 1977. The excavation at Giong Ca Vo site. Journal of Southeast Asian Archaeology 17: 30–37

- ^ Maria Halili (2010), Philippine History, ISBN 978-9712356360, Rex Books, 2nd Edition, pp. 46–47

- ^ Mellie Leandicho Lopez (2008), A Handbook of Philippine Folklore, University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 978-9715425148, pp xxiv – xxv

- ^ Manuel, E. Arsenio (1963), A Survey of Philippine Folk Epics, Asian Folklore Studies, 22, pp 1–76

- ^ "The Indian in the Filipino - INQUIRER.net, Philippine News for Filipinos". Archived from the original on June 21, 2015. Retrieved August 12, 2015.

- ^ Adelaar, K. Alexander (1994). "Malay and Javanese loanwords in Malagasy, Tagalog and Siraya (Formosa)" (PDF). Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences of Southeast Asia.

Further reading

[edit]- El Sanscrito en la lengua Tagalog – T H Pardo de Tavera, Paris, 1887

- The Philippines and India – Dhirendra Nath Roy, Manila 1929 and India and The World – By Buddha Prakash, 1964.

- David Prescott Barrows (1914), A history of the Philippines at Google Books, pages 25–37

External links

[edit]- The Laguna Copperplate Inscription by Paul Morrow

- A Philippine Document from 900 A.D. by Hector Santos

- The Tagalog Language From Roots to Destiny by Jessica Klakring